We are not quite a full month into the new Persian year 1403, and already things have gone south. Drastically. On 1 April Israel bombed a gathering of IRGC Qods Force officers who were meeting in a building that may or may not have been part of Iran’s consulate, killing seven, including two generals. One of them, Brigadier General Mohammad Reza Zahedi, was a senior Qods Force officer and said by Iranian media to be the most senior Iranian officer killed since IRGC Qods Force commander Qasem Soleimani. Iranian leaders promised that they would retaliate, and so they did on 13 April, launching a layered attack of some 300 drones and cruise and ballistic missiles. Iranian officials claim that the attack was directed only at military targets, particularly the Nevatim air base which the Iranians identified as the launching point for the aircraft that struck their diplomatic compound in Damascus. In any event, the IDF claims that Israeli defenses, assisted by US, UK, French, and other partners, intercepted 99 percent of the Iranian drones and missiles, with only very minor damage to two Israeli air bases and no fatalities. US officials subsequently reported that roughly half of the Iranian missiles employed malfunctioned, either failing to launch or falling well short of Israel. The Iranian government was quick to declare “the matter concluded” and planned no further retaliation, but as of this writing, Western media are reporting that an Israeli military response may be “imminent.”

On the Backs of Camels

This column may well be overtaken by events, but it is worth asking how we got here. For some, the answer is self-evident: we are informed that Iran seeks to promote chaos, that it seeks to escalate the conflict, and that it wanted to “break the taboo of targeting Israeli territory.” Such explanations are indicative of the muddled thinking in American foreign policy circles, adulterated with policy agendas, moral judgments, and a tendency to view the Gaza conflict in a Manichaean frame. But, at the risk of unsettling the comfortable notion that we and our allies are undeniably on the side of the angels and our opponents are irredeemable reprobates, I would argue that Iranian leaders likely felt they had little choice but to respond to the Israeli strike in Damascus, and that they probably judged that the risky drone and missile attack they launched was the least bad option available to them.

First, we have argued before in this space that Iran’s approach to the Gaza conflict has been notable for its restraint. Its conduct bears this out. Iran and its clients have largely confined their attacks to Israeli positions along the border with Lebanon or two harassing rocket and drone strikes on US bases in the region—and these latter have ceased since 4 February. The Iranian client group that has been least constrained, the Houthis in Yemen, is also the least pliable of Iran’s allies. The Houthis have generated increased domestic support from their defiance of Israel and the West, and they have exulted in being bolder and more revolutionary than their Iranian patrons, so Iran’s ability to rein them in may be limited. Nonetheless, for the most part Iran’s Axis of Resistance has maintained its restraint despite the fact that in strict military terms the Israelis have since October inflicted far more damage and casualties on the Axis than the Axis has been able to inflict on Israel. According to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), between 7 October 2023 and 15 March 2024, Israel conducted nearly 4,000 attacks on Lebanon—overwhelmingly artillery, missile, or airstrikes—and suffered some 781 attacks by Hizballah and associated groups in Lebanon. The Hizballah and other attacks killed 22 Israelis, but the Israeli strikes killed 357 Lebanese—roughly 16 Lebanese deaths for every Israeli killed. Moreover, the Israelis, unlike Iran and Hizballah, have not confined their attacks to the Lebanese-Israeli border but have struck in the Bekaa, in South Beirut, and repeatedly in Syria. If Iran saw it in its interest to escalate the war, this would be the place that would have the most impact, forcing Israel to draw off more forces from Gaza. Iran has instead absorbed the punishment and continued calling for a ceasefire.

Because Tehran’s conduct of the war has been restrained and risk averse, something must have pushed the Iranian leadership to discard its caution and take the risk of striking Israel directly. The airstrike that killed Zahedi and other senior officers in Damascus was a significant proximate cause, but almost certainly was not by itself sufficient to provoke Iran to take such a risk. Rather, a set of external and internal pressures were building on the Iranian Nezam, pressing it to take some action. The strike in Damascus was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Battles Between Wars–a Familiar Feature of Middle East Conflicts

As noted above, since October Israel regularly and intensively has struck at will Iranian and Hizballah targets all over Lebanon and Syria. This is not something new but rather a continuation of the Israeli “Battle Between the Wars” strategy it has been following for more than a decade in a bid to limit the size of the Iranian military footprint there and restrict its ability to operate openly. Tehran has largely endured these strikes as the cost of operating in the Levant. But the pace and intensity of the Israeli strikes have been increasing, growing fourfold from 12 strikes in 2017 to 48 in 2022. A research center in Turkey reports that Israeli airstrikes again increased in 2023. In addition, the number of senior IRGC officers being targeted also increased; according to the center-right Iranian news site Farhikhtegan, during the past Iranian year (March 2023–March 2024), Israel “martyred” 17 IRGC officers, significantly more than the ten IRGC officers it killed during the previous nine years. Moreover, the seniority of the officers killed, including multiple generals, was alarming. One Iranian analyst fretted that Israel was targeting progressively more senior and prominent Iranian officials and worried about where it would stop. In short, the trend lines were headed in an alarming direction, and Tehran worried how it might deter Israel from its gradual escalation of attacks.

An Act of War by Any Other Name…

The airstrike on the Iranian diplomatic compound in Damascus and the killing of Zahedi and six other IRGC officers brought this external pressure to a head. First, in killing Zahedi, Israel struck down the IRGC Qods Force general commanding the Syria-Lebanon theater; this would be roughly equivalent to Iran assassinating the US Commander of CENTCOM. One Iranian analyst described Zahedi as Iran’s top man in West Asia and compared his assassination to that of the IRGC Qods Force Commander Qasem Soleimani or the chief of Iran’s nuclear program, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh. Zahedi’s seniority alone would be a strong incentive for retaliation—as indeed, Iran did after Soleimani’s extinction. But adding to the shock of the Israeli attack was the Iranian perception that their diplomatic mission had been struck. Iranian media considered this an unprecedented affront and portrayed it in the old-fashioned if erroneous terms of an attack on sovereign Iranian territory. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei himself said on 10 April, “Attacking our consulate is like attacking our soil.” It may seem rich to Western ears to hear an Iranian regime, which has a long history of attacks on diplomatic missions in Tehran and abroad, whine about an attack on one of its embassies. But it is perhaps no more ironic than those Western countries who champion “the rules-based international order” while also promising Israel “ironclad support” as it conducts a military campaign in Gaza that the International Court of Justice has judged may amount to genocide. The Islamic Republic has no monopoly on hypocrisy.

In short, from the Iranian perspective, Israel, which had been pressing the envelope for several years, finally crossed a redline by attacking an Iranian diplomatic mission and killing a very senior Iranian officer. Much as the United States and Israel have been intent for some time on “restoring deterrence” with Iran, Iran now felt an urgent need to restore deterrence with Israel. A hardline strategist close to the administration of President Ebrahim Ra’isi publicly asserted that the government had a fundamental responsibility to safeguard its citizens with a credible deterrent and warned that Iran’s actions so far had not deterred Israel.

Tease–Now Please–the Crowd

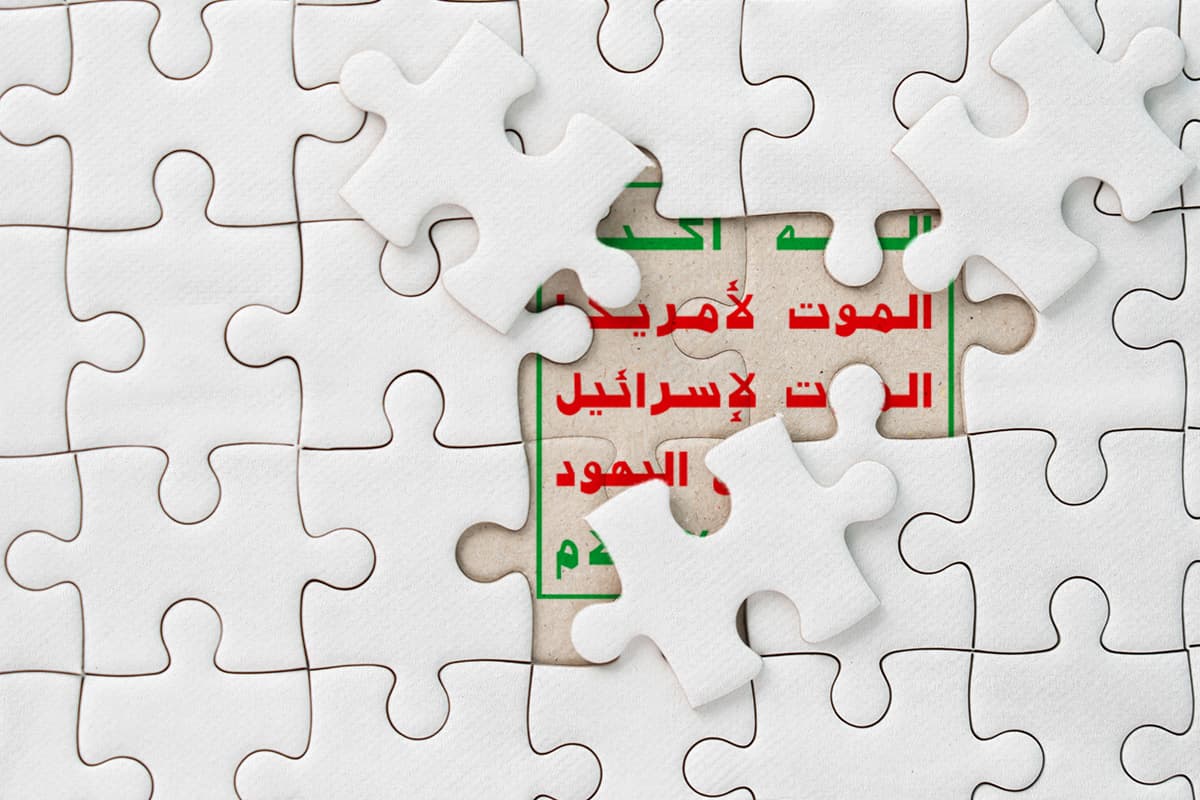

Tehran’s concern to prevent further escalation by Israel was compounded by mounting internal pressure on the regime. This pressure was in part the unintended—but foreseeable—consequence of Iranian leaders’ extravagant propaganda against Israel. Since the inception of the Islamic Republic, Tehran has viewed Israel as both a Western imperial imposition on the Muslim world and as a security threat to Iran. Its rhetoric, typically florid and bombastic, can be downright blood-curdling when it comes to Israel. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic, infamously declared Israel to be a “cancerous tumor” in the region, and current Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has employed that same epithet innumerable times, including this past February. IRGC Commander Major General Hosein Salami has predicted Israel’s “inevitable collapse” roughly once a month since Hamas launched the Gaza war on 7 October. Such trash talk is meant to reassure the regime’s supporters, both at home and in the Axis of Resistance. Tehran uses such posturing to display its readiness to defend the revolution and its allies and refute those who might think it is going soft. It is also part of Iranian deterrence, a means of inflating the apparent danger of attacking Iran the way a blowfish will swell into a spiky ball to warn off predators.

Unfortunately, decades of spouting such rubbish created expectations among the Islamic Republic’s devoted supporters, expectations frustrated by the regime’s restraint during the Gaza conflict. As we have noted before, hardline adherents of the regime have pointedly called out the Iranian government for the disconnect between its calls for Israel’s destruction and its cautious, measured actions in practice. The strike on Iran’s diplomatic compound in Damascus—an attack on “Iranian soil”—has only aggravated the frustration of the regime’s supporters and worsened their criticism. When Khamenei met with students last week, a Basiji “implored” him to send the Basij to fight in Palestine. The IRGC-affiliated news agency Fars ran an article in which the author, quoting Ferdowsi, implied that President Ebrahim Ra’isi was all talk and no action when it came to Israel. Even worse, those Iranians disillusioned or opposed to the regime had begun to mock its bluster and question its courage. Contempt was expressed on social media for Iran’s do-nothing military leadership, and graffiti appeared in Tehran accusing the government of being afraid of Israel.

Twenty-five years ago, when the Islamic Republic enjoyed broader support among the Iranian population, the government might have shrugged off both extremes, played one faction off the other, and remained confident it enjoyed sufficient support to pursue the policies it deemed best. But Khamenei has progressively sidelined and alienated different segments of the elite, starting with liberals, then Islamic reformists, then centrists and moderates, and most recently establishment conservatives deemed insufficiently supportive of the Nezam. Instead, through its program of “homogenizing” the political system, the Nezam is now dependent on that minority of the population—perhaps 25 to 30 percent of Iranian society—that remains traditionally pious and loyal to the Supreme Leader. Khamenei cannot afford to disillusion that remaining rump of hardline support that is now regime’s main constituency; if they lose faith in the regime, there will be no one to help defend it from challenges. At the same time, the regime cannot afford to have that dissatisfied majority of the population—which has with increasing frequency expressed its anger with episodes of civil unrest—lose its fear of the regime. If Iranians were coming to see the IRGC and security organs as quivering paper tigers, the risk that they would challenge the Nezam would grow. So, just as Iranian leaders worried that failure to act might embolden Israel to raise the pressure on Iran and cross more redlines, they also likely worried that a failure to respond to the Damascus strike would cause regime loyalists to lose faith and encourage domestic opponents to challenge the system.

The Nezam Telegraphs its Punches

Even then, with all the external and domestic pressure driving Tehran to respond to the Israeli strike, Iranian leaders sought to calibrate and conduct their retaliation in such a way as to minimize expansion of the war. If Israel had crossed a redline, Iran would have to cross a redline and attack Israel directly if it were to deter further Israeli action. But Iran took numerous measures to limit the risk of escalation. It clearly telegraphed its intentions to strike back, with Iranian leaders publicly promising retaliation. More importantly, Tehran is insistent that it warned its neighbors and the United States of the coming attack. Immediately following the Israeli strike, Foreign Minister Hosein Amir-Abdollahian announced via X on 1 April that “an important message” had been conveyed to the US via the Swiss Embassy regarding the Israeli attack. According to a subsequent tweet, Amir-Abdollahian met with several Europeans on 13 April and reiterated that “the necessary warning” had been passed to the United States. An Iranian journalist writing for a Western blog site reports that, according to a “well-informed source,” the Iranian message sent via the Swiss indicated that an Iranian response to the Israeli strike was imminent, and that the US should stay out of the fray and avoid further escalation. According to the same Iranian journalist and Reuters, Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan was an important intermediary who spoke with both his US and Iranian counterparts to discuss Iran’s planned operation. Finally, after the Iranian strike on Israel, Amir-Abdollahian claimed that Iran had warned neighboring countries of its intentions 72 hours before the attack. He also told reporters that on the night of the attack Tehran further informed the US that the Iranian attack would be limited, contained, and not aimed at US bases or personnel. After the attack, the Iranian foreign minister further asserted that Iran had not targeted any economic or population centers, a point reinforced by Iranian sources speaking to Amwaj Media who insisted that Iran “designed the attack to be de-escalatory” and “deliberately sought to prevent casualties.” There may be a fair amount of Iranian “spin” in such comments, but it is not inconsistent with what we know about the strike, and it is consistent with past Iranian actions, such as its missile strike on a US base in retaliation for the assassination of Soleimani in 2020. At a minimum, such messaging is not the behavior of someone seeking to escalate and intensify the crisis.

An unnamed US Administration official has refuted Iran’s claims that it provided the US 72 hours warning of its retaliatory strike; he insisted that “They did not give a notification, nor did they give any sense of … ‘these will be the targets, so evacuate them.’” He also argued that the Iranian intent was to be “highly destructive,” which may well be the case—but is not necessarily inconsistent with the claims that they sought only to target military sites and to avoid casualties. In their retaliatory strike on US bases in Iraq following the assassination of Soleimani, Iran’s missile barrage caused extensive damage to the bases but no loss of life. The US official also seems to set a rather high bar for the Iranian warning when he complains that the Iranians did not inform us of the specific targets of the strike. We would not expect the Iranians to provide such tactical information to the United States, only to confine their remarks to a warning that an attack was coming, coupled with efforts to clarify Iranian intent. But we would note that Turkish, Iraqi, and Jordanian officials all claim that Iran did in fact give them early warning of the attack last week, “including some details,” and the Wall Street Journal has reported that two days before the attack—that is, 11 April, the same day Amir-Abdollahian is reported to have spoken with the Turkish foreign minister—“Iranian officials briefed counterparts from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries on the outlines and timing of their plan for the large-scale strikes on Israel,” and the Saudis and Emiratis shared that information with the US. Iran may well not have provided early or sufficiently specific warning to the United States of its attack, but it beggars common sense to think that Iran would inform such countries as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Jordan, and Iraq and not expect at least one of them to share that information with Washington. Whether such information reached Washington in timely fashion—or at all—only those participants in the know can say for sure.

Iran’s Hollow Victory

In any event, Iran and the rest of us now wait to see whether and how the Israelis may choose to respond. Angered by Iran’s willingness to strike directly at Israel—and like the Houthis, disinclined to heed entreaties for restraint—the Israeli government may well strike back directly at Iran and commence a regional war. But even in the unlikely event that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu decides to follow the US advice to “take the win,” Iran will find its position weakened in this conflict. Its retaliatory strike, even if telegraphed, will be seen as something of a failure, even if it gains some admiration for attempting to strike back. Israel’s reputation for military superiority has been at least partially restored after the embarrassment of the 7 October attack. The attack has also caused Israel’s allies to emphasize their continuing support for Israel and to condemn Iran, when just a week before they were pressing the Netanyahu government to end the humanitarian disaster in Gaza and reach a ceasefire with Hamas. And despite Iran’s efforts to mend fences with its Arab neighbors, the limits of its influence with them have been revealed.

Even if the drone strike has reassured the regime’s shrinking base of popular support, it seems unlikely to have convinced the majority of disillusioned Iranians that the Nezam’s power remains unassailable. Following the attack, the Judiciary brought charges against a journalist for reporting (accurately) on 14 April that the value of the rial had dropped in the wake of the Iranian drone strike, and the IRGC Intelligence Organization issued a statement warning against any online activity—such as social media postings questioning the success of the Iranian operation—that was in support of the “Zionist entity.” Such measures do not suggest the Nezam is now more confident of its standing with the Iranian public.

Some of this almost certainly was foreseen by Iranian officials—analysts interviewed in the Iranian media before Iran’s retaliatory strike recognized that such an action might well shift attention away from the plight of the Palestinians and toward the threat perceived to come from Iran. Iran’s extensive diplomatic contacts in the past week likely were intended to limit the potential for its retaliatory strike to damage its improved relations in the region—even if that risked providing additional warning to the US and Israel. That Iran could foresee such consequences and yet went ahead with the attack points to an Iran that was not eager to escalate, nor exploiting the crisis to reshape the region, but instead an Iran that had only bad and worse options to try to counter Israel’s steadily mounting military pressure. We may soon find out whether Iran has succeeded in limiting the potential for escalation or is instead about to reap the whirlwind.